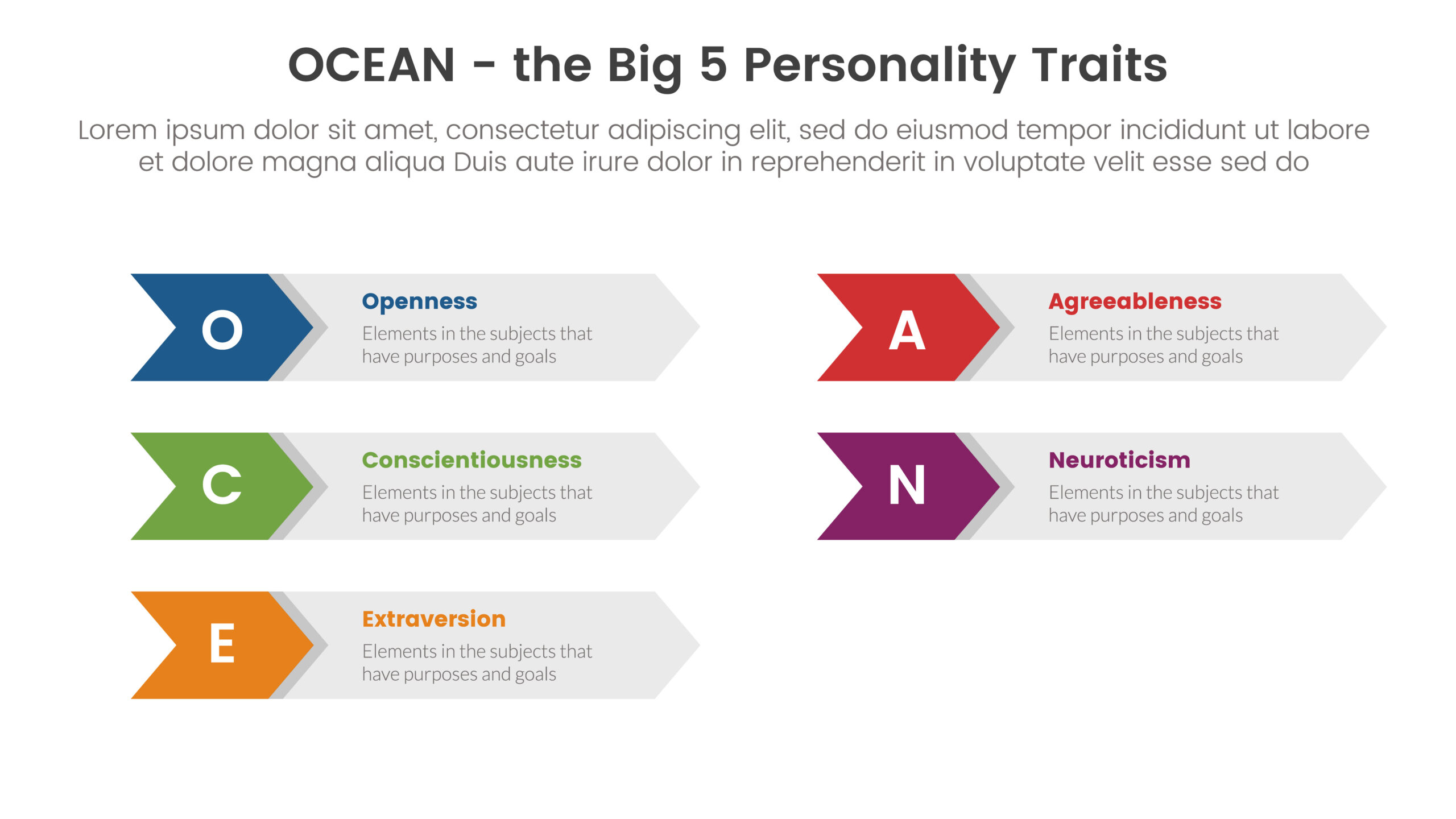

Understanding the Big Five Personality Traits: A Comprehensive Guide to the OCEAN Model

The Big Five Personality Traits, also known as the Five-Factor Model (FFM), represent a widely recognized and extensively studied framework for understanding personality in psychology. This model describes individual differences in personality across five broad dimensions: Openness to Experience, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism. Each trait exists on a spectrum, with individuals varying in how strongly they express each one. The model is used to help people understand themselves and how they compare to others. Companies sometimes use this model to predict how employees or potential candidates might relate to others and handle stress.

The Big Five model has broad support and originated in the United States before being translated into many languages and used in various countries. These traits describe an individual’s behavior, emotions, and thinking patterns and are often used to predict life outcomes such as job performance and well-being. While the Big Five are broad categories encompassing many personality-related terms and facets, criticisms suggest that the model may oversimplify personality and that more specific traits or more than five traits might be needed to fully encompass personality. The HEXACO model, for instance, is an alternative developed through cross-cultural research that adds a Honesty-Humility trait and slightly modifies Agreeableness and Neuroticism.

Let’s explore each of the five traits in detail:

Openness to Experience

Openness to Experience is characterized by a person’s tendency to seek out new experiences and to be willing to explore ideas, values, emotions, and sensations that differ from their previous experience or established preferences. It reflects curiosity, creativity, and a willingness to explore new ideas or activities.

- High Openness: Individuals scoring high on Openness enjoy variety, embrace change, and are likely to engage in creative or unconventional pursuits. They are characterized by imagination, creativity, and a tendency to indulge in daydreams (Fantasy facet). They appreciate art, music, and beauty (Aesthetics facet), have emotional awareness and sensitivity (Feelings facet), are adventurous and willing to take risks (Actions facet), are intellectually curious and open-minded (Ideas facet), and are open to alternative belief systems (Values facet). People high in openness are associated with increased creativity, curiosity, adaptability, mental flexibility, and acceptance of others. They are often found discussing abstract concepts like philosophy or art and seeking diverse perspectives.

- Low Openness: Individuals scoring low on Openness prefer routine and tradition and value practicality over novelty.

Openness has been widely studied in cultural and organizational psychology. It correlates with individuals’ career advancement into managerial and professional roles and is associated with managing conflicting cultural values and adapting to new cultural contexts, which is crucial for success in multicultural environments. High openness is also linked to positive outcomes in professional settings, including better job performance and organizational citizenship behavior.

The neurobiological basis of openness involves the interaction among reward systems, the default mode network (DMN), and the executive control network (ECN). This interaction supports openness by increasing mental flexibility, responsiveness to reward and novelty, and incorporating creativity into thought processes, decision-making, and behavior. While moderate openness supports well-being, extremely high levels have been linked to a greater risk of psychotic-like experiences.

Openness can be measured using standardized questionnaires like the NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI) or the HEXACO personality inventory.

Conscientiousness

Conscientiousness is a trait that describes an individual as disciplined, careful, organized, detail-oriented, and thoughtful.

- High Conscientiousness: People high in conscientiousness have good impulse control, which helps them complete tasks and achieve goals. They are organized, disciplined, detail-oriented, thoughtful, and careful. They are self-starters, keen to get work done, meet deadlines, and require little hand-holding.

- Low Conscientiousness: People low in conscientiousness may struggle with impulse control, leading to difficulty completing tasks. They tend to be more disorganized, may dislike too much structure, and might engage in impulsive and careless behavior. Low conscientiousness predicts juvenile delinquency.

Conscientiousness is the strongest predictor among the Big Five traits for job performance. High scores predict better high school and university grades. This trait is also strongly linked to better financial planning, saving money, and long-term financial success. Conscientious individuals are more likely to have successful long-term relationships and lower divorce rates. Studies show conscientious people are less likely to use their phones and use them for shorter durations. Conscientiousness is considered one of the most important factors for a leader, particularly under stressful situations where responsibility and reliability are key.

Extraversion

Extraversion, sometimes called extroversion, reflects how you interact socially. It describes sociability, assertiveness, and cheerfulness. The concept was introduced by Carl Gustav Jung and exists on a continuum.

- High Extraversion: Individuals high in extraversion are more outgoing and talkative, thriving in social situations. They tend to have a wide social circle, find it easy to make friends, like starting conversations, and feel comfortable arguing and debating their opinions. They seek excitement and generally enjoy being around people. Extroverts are energized by social interaction, enjoy group work, prefer talking over writing, and are typically confident and talkative. They can easily verbalize their emotions and opinions, even around strangers, and enjoy working in larger groups. Extroverts can organize events, spearhead conversations, and become leaders. They value others’ opinions and work out their thought processes with individuals. High extraversion scores would do well in roles where they thrive off interaction, such as sales, marketing, and PR, and are suited for supervisory positions. Studies suggest extroverts outnumber introverts about three to one. They use their phones more frequently once checked. Extraverts are successful in the workplace, with adaptability, positive attitudes, and good interpersonal skills. They build rapport, boost company morale, and are associated with promotions, higher salaries, and leadership positions.

- Low Extraversion: Individuals scoring lower on extraversion are more introverted or reserved. They may feel tired after socializing, prefer solitude, need more alone time, feel uncomfortable interacting with strangers, dislike small talk, and tend to avoid large groups. Being the center of attention can be taxing. Introverts find energy in alone time and feel more comfortable in solitary or low-stimulus environments. They may find verbal communication challenging and prefer writing, drawing, or listening to music. They tend to be more logical and detail-oriented, practical decision-makers, and valuable workers in jobs with less social interaction, such as writing, engineering, or accounting.

It’s a continuum, and some people fall in the middle as ambiverts or introverted extroverts, capable of leveraging traits from both ends. While Western cultures may be biased towards extroversion, Eastern cultures tend towards introversion, which focuses more on group success.

Agreeableness

Agreeableness can be described as a personality trait encompassing being cooperative, polite, kind, and friendly.

- High Agreeableness: People high in agreeableness are more trusting, affectionate, altruistic, and generally display more prosocial behaviors. They are particularly empathetic and show great concern for the welfare of others, often being the first to help those in need. They are less me-centric and more we-centric, looking for the common good. They are quick to listen to others’ opinions and look for harmony instead of discord. Agreeable people don’t insult others, question their motives or intentions, or think they are better than others; they see everyone as their equal and are quick to empathize and respect others. These people-oriented individuals usually have good social skills. They make good teammates and are not out to outshine everyone else. You might find agreeable types in sales positions or human resources. High agreeableness scores strongly predict performance in healthcare and clerical occupations.

- Low Agreeableness: The opposite end of the spectrum includes being suspicious and uncooperative.

Agreeableness can change over time, with people tending to become more agreeable as they get older. In the HEXACO model, anger/even-temper becomes associated with the Agreeableness trait. Some research suggests that less agreeable individuals may have better preserved cognition.

Neuroticism

Neuroticism is a core personality trait characterized by emotional instability, irritability, anxiety, self-doubt, depression, and other negative feelings. It exists on a continuum, with people falling high, low, or in the middle.

- High Neuroticism: People higher in neuroticism tend to be anxious and pessimistic. They experience emotional instability, irritability, anxiety, self-doubt, depression, and negative feelings. While it can cause problems, people high in neuroticism tend to be more creative, spend time thinking about what others are thinking and feeling, and have emotional depth and empathy. They are good at spotting dangers and solving problems and are likely to be the ones looking out for others and being sensitive to their feelings. Potential contributing factors include brain function (lower oxygen in the lateral prefrontal cortex after seeing unpleasant images), childhood trauma, climate, and genetics. It has also been argued that neuroticism may have evolutionary roots, offering a survival advantage by making individuals hypersensitive to threats. Women tend to score higher than men in many countries, though the gender gap appears smaller online where anonymity reduces worries about others’ opinions.

- Low Neuroticism: Individuals scoring low on neuroticism are typically calm and confident.

Individuals struggling with feelings of neuroticism can seek professional help, such as Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) or Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), to manage negative thoughts and emotions. Finding ways to relieve stress, such as exercise, meditation, yoga, or art, can also help. High neuroticism doesn’t inherently make someone a bad person; the positive aspects can be combined with inner work to channel behavior constructively. Neuroticism shows a negative relationship with extrinsic career success. The overlap of questions related to neuroticism with items in the DSM-5 used for diagnosing mental disorders has raised concerns about potential discrimination in hiring based on personality tests.

Measuring the Big Five

The Big Five personality traits are typically measured using standardized questionnaires or inventories, where individuals rate themselves on various statements or adjectives. Assessments like the NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI, including versions like NEO-PI-R and NEO-FFI) or the Big Five Inventory (BFI) provide scores for each trait, allowing for a personality profile. The HEXACO personality inventory is another commonly used measure.

However, self-report personality inventories are vulnerable to the “social desirability bias,” where respondents answer in a way they believe will be viewed favorably, potentially compromising accuracy.

Factors Influencing Traits

Personality traits are influenced by both nature and nurture. Studies, including those on twins, suggest a significant heritability component for each of the Big Five traits. For example, one study suggested heritability estimates ranging from 41% for Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, and Neuroticism to 61% for Openness.

Furthermore, personality can change over time. Research indicates that people tend to become more agreeable, conscientious, and emotionally stable (lower in neuroticism) as they age. Changes in openness to experience can also follow from upward job changes into managerial and professional positions. Neuroplasticity allows for some flexibility in traits over time.

Limitations and Criticisms

Despite its widespread acceptance, the Big Five model has several limitations. Some experts argue that the FFM oversimplifies personality and that additional traits, such as humility (included in the HEXACO model), are necessary for a complete picture.

The predictive value of the FFM can depend on the job type; for instance, high agreeableness predicts performance in healthcare and clerical jobs but not sales positions. The model was largely developed by studying individuals from WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Developed) countries, which can affect the accuracy and interpretability of results when applied to individuals from other cultures.

As mentioned, self-report inventories are susceptible to social desirability bias. Concerns also exist that using Big Five personality tests in hiring may be discriminatory, particularly against individuals from non-WEIRD countries or those with mental health conditions due to the overlap of neuroticism-related questions with diagnostic criteria. Organizations must be aware of these shortcomings to leverage the benefits of the tests while ensuring diverse and inclusive practices.

Conclusion

The Big Five Personality Traits model provides a widely recognized framework for understanding the core dimensions of human personality: Openness to Experience, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism. These traits help describe how individuals think, feel, and behave and offer valuable insights into potential life outcomes, including career success and relationships. Ongoing research continues to explore the neurobiological underpinnings of these traits and their implications across different cultures. While the model is a powerful tool, it is essential to be mindful of its limitations, such as potential oversimplification and vulnerabilities in measurement and application, particularly in diverse or clinical contexts.